Appendices

1997 by J. Gregory Payne, Ph.D.

1

Richard M. Nixon's Speech of Thursday, April 30,

1970

videos of the speech

"Good evening my fellow Americans.

Ten days ago in my report to the nation on Vietnam I announced the decision to withdraw an additional 150,000 Americans from Vietnam over the next year. I said then that I was making that decision despite our concern over increased enemy activity in Laos, in Cambodia and in South Vietnam.

And at that time I warned that if I included that if increased enemy activity in any of these areas endangered the lives of Americans remaining in Vietnam, I would not hesitate to take strong and effective measures to deal with that situation.

Despite that warning, North Vietnam has increased its military aggression in all these areas, and particularly in Cambodia.

After full consultation with the National Security Council, Ambassador Bunker, General Abrams and my other advisers, I have concluded that the actions of the enemy in the last 10 days clearly endanger the lives of Americans who are in Vietnam now and would constitute an unacceptable risk to those who will be there after the withdrawal of another 150,000.

To protect our men who are in Vietnam, and to guarantee the continued success of our withdrawal and Vietnamization program, I have concluded that the time has come for action.

Tonight, I shall describe the actions of the enemy, the actions I have ordered to deal with that situation, and the reasons for my decision.

Cambodia--a small country of seven million people--has been a neutral nation since the Geneva Agreement of 1954, an agreement, incidentally, which was signed by the Government of North Vietnam.

American policy since then has been to scrupulously respect the neutrality of the Cambodian people. We have maintained a skeleton diplomatic session of fewer than 15 in Cambodia's capital, and that only since last August.

For the previous four years, from 1965 to 1969 we did not have any diplomatic mission whatever in Cambodia, and for the past five years we have provided no military assistance whatever and no economic assistance to Cambodia.

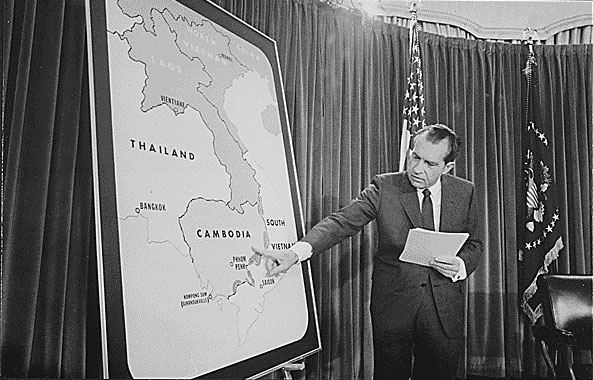

North Vietnam, however, has not respected that neutrality. For the past five years, as indicated on this map, as you see here, North Vietnam has occupied military sanctuaries all along the Cambodian frontier with South Vietnam. Some of these extend up to 20 miles into Cambodia.

The Sanctuaries are in red, and as you note they are on both sides of the border.

They are used for hit and run attacks on American and South Vietnamese forces in South Vietnam. These Communist-occupied territories contain major base camps, training sites, logistics facilities, weapons and ammunition factories, airstrips and prisoner of was compounds.

And for five years neither the United States not South Vietnam has moved against these enemy sanctuaries because we did not wish to violate the territory of a neutral nation.

Even after the Vietnamese Communists began to expand these sanctuaries four weeks ago, we counseled patience to our South Vietnamese allies and imposed restraints on our own commanders.

In contrast to our policy the enemy in the past two weeks has stepped up his guerrilla actions and is concentrating his main force in these sanctuaries that you see in this map, where they are building up to launch massive attacks on our forces and those of South Vietnam.

North Vietnam in the last two weeks has stripped away all pretense of respecting the sovereignty or the neutrality of Cambodia. Thousands of their soldiers are invading the country from the sanctuaries. They are encircling the capital, Pnompenh. Coming from these sanctuaries as you see here, they have moved into Cambodia and are encircling the capital.

Cambodia, as a result of this, has sent out a call to the United States, to a number of other nations, for assistance. Because if this enemy effort succeeds, Cambodia would become a vast enemy staging area and a springboard for attacks on South Vietnam along 600 miles of frontier: a refuge where enemy troops could return from combat without fear of retaliation.

North Vietnamese men and supplies could then be poured into that country, jeopardizing not only the lives of our men but the people of South Vietnam as well.

Now confronted with this situation we had three options:

First, we can do nothing. Now, the ultimate result of that course of action is clear. Unless we indulge in wishful thinking, the lives of Americans remaining in Vietnam after our withdrawal of 150,000 would be gravely threatened.

Let us go to the map again.

Here is South Vietnam. Here is North Vietnam. North Vietnam already occupies this part of Laos. If North Vietnam already occupied this whole band in Cambodia or the entire country, it would mean that South Vietnam was completely outflanked and the forces of Americans in this area as well as the South Vietnamese would be in an untenable military position.

Our second choice is to provide massive military assistance to Cambodia itself and unfortunately, while we deeply sympathize with the plight of seven million Cambodians whose country has been invaded, massive amounts of military assistance could not be rapidly and effectively utilized by this small Cambodian Army against the immediate trap.

With other nations we shall do our best to provide the small arms and other equipment which the Cambodian Army of 40,000 needs and can use for its defense.

But the aid we will provide will be limited for the purpose of enabling Cambodia to defend its neutrality and not for the purpose of making it an active belligerent on one side or the other.

Our third choice is to go to the heart of the trouble.

And that means cleaning out major North Vietnamese and Vietcong-occupied territories, these sanctuaries which serve as bases for attacks on both Cambodian and American and South Vietnamese forces in South Vietnam.

Some of these, incidentally, are as close to Saigon as Baltimore is to Washington. This one, for example, is called the Parrots' Beak - it's only 33 miles from Saigon.

Now faced with these three options, this is the decision I have made. In cooperation with the armed forces of south Vietnam, attacks are being launched this week to clean out major enemy sanctuaries on the Cambodian-Vietnam border. A major responsibility for the ground operation is being assumed by South Vietnamese forces.

For example, the attacks in several areas, including the parrot's beak, that I referred to a moment ago, are exclusively South Vietnamese ground operations, under south Vietnamese command, with the United States providing air and logistical support.

There is one area, however, immediately above the parrot's beak where I have concluded that a combined American and south Vietnamese operation is necessary.

Tonight, American and south Vietnamese units will attack the headquarters for the entire Communist military operation in South Vietnam. The key control center has been occupied by the North Vietnamese and Vietcong for five years in blatant violation of Cambodia's neutrality.

This is not an invasion of Cambodia. The areas in which these attacks will be launched are completely occupied and controlled by North Vietnamese forces.

Our purpose is not to occupy the areas. Once enemy forces are driven out of these sanctuaries and once their military supplies are destroyed, we will withdraw.

These actions are in no way directed to security interests of any nation. Any government who chooses to use these actions as a pretext for harming relations with the United States will be doing so on its own responsibility and on its own initiative and we will draw the appropriate conclusions.

And now, let me give you the reasons for my decision.

A majority of the American people, a majority of you listening to me are for the withdrawal of our forces from Vietnam. The action that I have taken tonight is indispensable for the continuing success of the withdrawal program.

A majority of the American people want to end this war rather than have it drag on interminably.

The action I have taken tonight will serve that purpose.

A majority of the American people want to keep the casualties of our brave men in Vietnam at an absolute minimum.

The action I take tonight is essential if we are to accomplish that goal.

We take this action not for the purpose of expanding the war in Cambodia, but for ending the was in Vietnam, and winning the just peace we all desire.

We have made and will continue to make every possible effort to end this war through negotiation at the conference table rather than through more fighting in the battlefield.

Let's look again at the record.

We stopped the bombing in North Vietnam. We have cut air operations by over 20 per cent. We've announced the withdrawal of over 250,000 of our men. We've offered to withdraw all of our men if they'll withdraw theirs. We've offered to negotiate all issues with only one condition: and that is that the future of South Vietnam be determined, not by North Vietnam, and not by the United States, but by the people of South Vietnam themselves.

The answer of the enemy has been intransigence at the conference table, belligerence at Hanoi, massive military aggression in Laos and Cambodia and stepped-up attacks in Laos and Cambodia designed to increase American casualties.

This attitude has become intolerable.

We will not react to this threat of American lives merely by plaintive diplomatic protests.

If we did, credibility of the United States would be destroyed in every area of the world where only the power of the United States deters aggression

Tonight, I again warn the North Vietnamese that if they continue to escalate the fighting when the United States is withdrawing its forces, I shall meet my responsibility as commander in chief of our armed forces to take the action I consider necessary to defend the security of our American men.

The action I have announced tonight puts the leaders of North Vietnam on notice that we will be patient in working for peace. We will be conciliatory at the conference table, but we will not be humiliated. We will not be defeated.

We will not allow American men by the thousands to be killed by an enemy from privileged sanctuary.

The time came long ago to end this was through peaceful negotiations. We stand ready for those negotiations. We've made major efforts many of which remain secret.

I say tonight all the offers and approaches made previously remain on the conference table whenever Hanoi is ready to negotiate seriously.

But if the enemy response to our most conciliatory offers for peaceful negotiation continues to be to increase its attacks and humiliate and defeat us, we shall react accordingly.

My fellow Americans, we live in an age of anarchy, both abroad and at home. We see mindless attacks on all the great institutions which have been created by free civilizations in the last 500 years. Even here in the United States, great universities are being systematically destroyed.

Small nations all over the world find themselves under attack from within and from without. If when the chips are down the world's most powerful nation-the United States of America-acts like a pitiful, helpless giant, the forces of totalitarianism and anarchy will threaten free nations and free institutions throughout the world.

It is not our power but our will and character that is being tested tonight.

The question all Americans must ask and answer tonight is this:

Does the richest and strongest nation in the history of the world have the character to meet a direct challenge by a group which rejects every effort to win a just peace, ignores our warning, tramples on solemn agreements, violates the neutrality of an unarmed people and uses our prisoners as hostages?

If we fail to meet this challenge all other nations will be on notice that despite its overwhelming power the United States when a real crisis comes will be found wanting.

During my campaign for the Presidency, I pledged to bring Americans home from Vietnam. They are coming home. I promised to end this war. I shall keep that promise. I promised to win a just peace. I shall keep that promise.

We shall avoid a wider war, but we are also determined to put an end to this war.

In this room, Woodrow Wilson made the great decisions which led to victory in World War I.

Franklin Roosevelt made the decisions which led to our victory in World War II.

Dwight D. Eisenhower made decisions which ended the war in Korea and avoided was in the Middle East.

John F. Kennedy in his finest hour made the great decision which removed Soviet nuclear missiles from Cuba and the western hemisphere.

I have noted that there has been a great deal of discussion with regard to this decision that I have made. And I should point out that I do not contend that it is in the same magnitude as the decisions I have just mentioned.

But between those decisions and this decision, there is a difference that is very fundamental. In those decisions the American people were not assailed by counsels of doubt and defeat from some of the most widely known opinion leaders of the nation.

I have noted, for example, that a Republican Senator has said that this action I have taken means that my party has lost all chance of winning the November elections, and others are saying today that this move against enemy sanctuaries will make me a one-term President.

No one is more aware than I am of the political consequences of the action I've taken. It is tempting to take the easy political path, to blame this war on previous Administrations, and to bring all of our men home immediately-regardless of the consequences, even though that would mean defeat for the United States; to desert 18 million South Vietnamese people who have put their trust in us; to expose them to the same slaughter and savagery which the leaders of North Vietnam inflicted on hundreds of thousands of North Vietnamese who chose freedom when the Communists took over North Vietnam in 1954.

To get peace at any price now, even though I know that a peace of humiliation for the United States would lead to a bigger war or surrender later.

I have rejected all political considerations in making this decision. Whether my party gains anything in November is nothing compared to the lives of 400,000 brave Americans fighting for our country and for the cause of peace and freedom in Vietnam.

Whether I may be a one term President is insignificant compared to whether by our failure to act in this crisis the United States proves itself to be unworthy to lead the forces of freedom in this critical period in world history.

I would rather be a one term President and do what I knew was right than be a two- term President at the cost of seeing America become a second-rate power and to see this nation accept the first defeat in its proud 190-year history.

I realize in this war there are honest deep differences in this country about whether we should have become involved, that there are differences to how the war should have been conducted.

But the decision I announce tonight transcends those differences, for the lives of American men are involved. The opportunity for 150,000 Americans to come home in the next 12 months is involved. The future of 18 million people in South Vietnam and 7 million people in Cambodia is involved, the possibility of winning a just peace in Vietnam and in the Pacific is at stake.

It is customary to conclude a speech from the White House by asking support for the President of the United States.

Tonight, I will depart from that precedent. What I ask is far more important. I ask for your support for our brave men fighting tonight halfway around the world, not for territory, not for glory but so that their younger brothers and their sons and your sons can have a chance to grow up in a world of peace and freedom, and justice.

Thank you and good night."

2

Governor Rhodes' Speech at Press Conference

Kent, Ohio

May 3, 1970

Kent Fire House

We're seeing at, uh, the city of Kent, especially, probably the most vicious form of campus oriented violence yet perpetrated by dissident groups and their allies in the state of Ohio. For this reason most of the dissident groups have operated within the campus. This has moved over to where they have threatened and intimidated merchants and people of this community. Now it ceases to be a problem of camp- of the colleges in Ohio. This now is the problem of the state of Ohio and I want to assure you that we are going to employ every force of law that we have under our authority, not only to get to the bottom of the situation here at Kent, on the campus, in the city and we have asked the complete cooperation of the district attorney of the federal government because federal supplies were burned and destroyed in the ROTC building and these people after we can find them, after a complete investigation will be turned over to the federal government. We have asked the county prosecutor for a complete and comprehensive investigation and there's some people now out on probation that there has been a strong word to the fact that they have participated in this. And we're going to put a stop to this for this reason: the same group that we're dealing with here today, and there's three or four of them, they only have one thing in mind, that is to destroy higher education in Ohio. And if they continue this, and continue what they're doing, they're going to reach their goal for the simple reason: that you cannot continue to set fires to buildings that are worth five and ten million dollars because you cannot get replacement from the high general assembly. And last night I think that we have seen all forms of violence, the worst, and when they start taking over communities, this is when we're going to use every part of the law enforcement (agencies?) of Ohio to drive them out of Kent.

We're going to make two recommendations to the High General Assembly. Now we've had this in Miami, in Oxford, Ohio, also Ohio State University and we've had thirty-two police officers injured and a couple very severe. We have these same groups going from one campus to the other and to use a university state supported by the tax payer of Ohio as a sanctuary. And in this they make definite plans of burning, destroying, and throwing rocks at police and at the national guard and the highway patrol. We're asking the legislature that any person throwing a rock, brick or stone at a law enforcement at a law enforcement agent of Ohio, a sheriff, policeman, highway patrol, national guard becomes a felony.

And secondly we're going to ask for legislation that any person in the administrative

side or as a student, if these people are convicted, whether a misdemeanor

or a felony, participating in a riot, they're automatically dismissed, there's

no hearing, no recourse and they cannot enter another state university in

the state of Ohio. We are going to eradicate the problem. We're not going

to treat the symptoms. And as long as this continues, higher education in

Ohio is in jeopardy. And if they are continued to give permissive consent,

they will destroy higher education in this state.

3

The Justice Department's Summary of FBI Reports

This report is a summary, prepared sometime in July 1970 by the Justice Department's Civil Rights division, of the FBI reports on Kent State. The purpose of such summaries is to provide guidelines for possible prosecution under federal law. The summary was also made available to the Ohio authorities. Excerpts from this report appeared in The New York Times in November 1970.

Kent State University is located in the small University town of Kent in the northeastern portion of Ohio, approximately ten miles northeast of Akron and thirty miles southeast of Cleveland. Approximately 20,000 students are enrolled at this institution: 85% of whom are graduates of Ohio high schools.

The only previous major turbulence at Kent State occurred in November, 1968 and April, 1969. In November, 1968, black and white students staged a sit-in to protest the efforts of the Oakland, California Police Department to enlist new recruits from the student body of Kent State. To our knowledge, no personal or property damage occurred at this time.

In April, 1969, the Kent State Chapter of SDS disrupted a meeting being held in the Music and speech Building. Fifty-eight students were arrested-among them were four leaders of SDS. Subsequently, SDS was banned from the Kent State Campus. During the 1968-69 school year, national leaders of SDS, including Mark Rudd and Bernadine Dohrn, had visited the Campus, presumably because SDS was then a recognized campus activity. On Wednesday, April 29, 1970, the four SDS leaders imprisoned for their part in the April 29, 1969 melee were released from jail. Although there has been speculation in local law enforcement circles that they participated or even planned the confrontation occurring May 1-4, 1970, there is no evidence to substantiate this. Similarly, although Jerry Rubin made a speech at Kent State on April 10, 1970, no connection has been made between that speech and the May 1-4 weekend. To our knowledge, from April, 1969 until May 1, 1970, Kent State University experienced no problems with student unrest.

On April 30, 1970, President Richard Nixon made a televised address to the nation and at that time announced that he was committing United States troops from Viet Nam into specified areas of Cambodia. The reaction of some Kent State students and faculty was immediate.

On Friday, May 1, at 12:00 noon rally, sponsored by a group of Kent State University history graduate students, self styled The World Historians Opposed to Racism and Exploitation (WHORE), was held on the commons at the Victory Bell in response to the President's announcement of the previous evening. This rally drew approximately 500 faculty and students. The general theme of the speeches was that the President had disregarded the limits of his office imposed by the Constitution of the United States and that, as a consequence, the Constitution had become a lifeless document, murdered by the President. As a symbolic act, a copy of the Constitution was buried at the base of the Victory Bell. Anti-war sentiment was articulated by the speakers. One student, supposedly a Viet Nam veteran, burned what was purported to be his military discharge papers. The rally disbanded without exhortation to more violent means of protest and with an expressed desire that another rally be held at 12:00 noon on Monday, May 4, 1970, to further protest the war in Viet Nam and the invasion of Cambodia.

At 3:00 p.m. on the same day, May 1, a rally was held by the Black United Students (BUS), a small organization composed of some of the Negro students on the Kent State Campus. Speakers at this rally were Negro students from Ohio State University. In general, these speakers concerned themselves with issues primarily concerning the black community, and not with the issue of the war. This meeting was sparsely attended and also broke up peacefully.

No further rallies or assemblies occurred on the Kent State Campus on Friday.

On Friday night, May 1, 1970, the scene shifted to North Water Street, just off Main Street in the heart of downtown Kent-an area lined with bars and taverns frequented by students, but also by non-students. We are not sure how the incident on this night started. At about 11:00 p.m., a small crowd gathered on the street between two bars, one known as "J. B." and the other known as "The Kove." Anti-war slogans were chanted. A police car cruised through the area and was greeted with applause. As it left the area, the applause grew. The police car continued on a number of other occasions to pass by the students. On the fourth or fifth pass, at about 11:27 p.m. some people threw beer bottles and glasses at the car, which kept going and did not return. The street was then blocked off by the people and a bonfire was built in the street. It seems certain that not all of the persons in the street were certain that not all of the persons in the street were students. There were members of a motorcycle gang present at some time during the night's activities but statements conflict on the question of whether they participated in the incident.

At 11:41 p.m., all twenty-one Kent Policemen were summoned to duty. The Stow Police Department was alerted as well as was the Portage Count Sheriff's Department, which sent 80-90 regular and special deputies to Kent. Apparently after the law enforcement officers arrived on the scene, the crowd in the street, now numbering probably between 400 and 500, began to break windows in various business establishments in the area. One jewelry store was looted. At 12:30 a.m., May 2, 1970, Mayor Satrom proclaimed the City of Kent to e in a State of Civil Emergency. A 6:00 p.m. to 8:00 p.m. curfew was established in the town and all establishments selling alcoholic beverages were closed and the sale of alcohol, firearms, ammunition and gasoline was prohibited. AT 1:42 a.m. police used tear gas to move the students from the downtown area toward the Campus. At 2:27 a.m., the students were reported as being on the Campus. By 3:00 a.m., two Ohio Highway Patrolmen had arrived in Kent to view the incident, but by this time, the disturbance was over.

The damage to the businesses in the City of Kent was first estimated at approximately $50,000 by the Mayor. We do not know exactly how many windows were broken nor how many establishments were damaged. The Mayor subsequently revised his earlier estimate of $50.000 in property damage to $15,000. Newspapers have reported that ten to fifteen buildings had windows broke. No fire, except for the street fire, was related to the disturbance. Four or five policeman or sheriff's deputies were injured by rocks thrown by students, but none required hospitalization. fifteen persons were arrested, all of whom gave Ohio addresses.

On Saturday morning, May 2, a meeting was held among University officials, city officials and a representative of the National Guard. Although University officials regarded the action as unnecessary, in that they felt that local law enforcement personnel could cope with any situation that might arise, the Mayor, other city officials and the National Guard representative decided at that time to put a company of 110 National Guardsmen on standby. Two other such meetings were held during the day. We do not know what was discussed or decided at the subsequent meetings. Apparently, at 10:00 a.m. the Sheriff of Portage County orally requested the assistance of national Guard troops. We do not know whether the Sheriff's action was taken independently of the decision made at the Saturday morning meetings.

Mayor Satrom at 5:00 p.m., Saturday, May 2, 1970, telephoned "Columbus" (presumably Governor Rhodes), and advised that the local law enforcement agencies (apparently excluding the Highway Patrol) could not cope with the situation and requested national Guard troops to "assist in restoring law and order in the City of Kent...and Kent State University.."(1) This request was also made in writing to the Commander of Troops, Ohio National Guard. Governor Rhodes orally authorized the use of the National Guard in the City of Kent. No University official was consulted prior to Mayor Satrom's request. Companies A and C, 145th Infantry and Troop G, 107th Armored Cavalry Ohio National Guard, mobilized on April 29, 1970, in connection with the Teamster strike and on active duty status since that date, were alerted and prepared to move to Kent. Upon receiving this order to move, Company A was immediately given a one or two hour lesson in riot control. Troops began arriving in Kent at 7:00 p.m.

Additionally, on May 2, an injunction affecting the University was entered in the Court of Common leas in the case of State of Ohio, ex rel Board of Trustees of Kent State University v. Michael Weekly and "John Doe," Numbers 1-5000.(2) The order enjoined the defendants from breaking windows, defacing buildings with paint, starting any fires on campus and damaging or destroying any property owned by the University. It is not known who sought the injunction nor at what time it was entered, nor if the injunction was served upon any person or disseminated in any way.

Although things were quiet on the Kent State University Campus, during the day on May 2, word had passed among the students that a rally on the commons was planned that night for 8:00 p.m. At 7:30 p.m., the Ohio State Highway Patrol was notified that approximately 600 had gathered on the commons. At 8:00 p.m., the sheriff's department sent 60 men to Kent. The crowd left the commons and made the rounds of a number of dormitories in an effort to enlist additional members in their group. After their efforts to more students, the crowd moved back to the commons.

The wooden ROTC building, a target for some students because of its symbolism of U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia, was located on the western portion of the commons. It became the focal point of the demonstration. Rocks were thrown by some persons at the ROTC building, beginning at 8:10 p.m. Subsequently, rocks and a wastebasket were thrown through windows. Flares were thrown in the windows and on top of the building with no fire resulting. One person attempted to set the curtains in the ROTC building on fire. This attempt was unsuccessful. An American flag was burned. One photographer was assaulted, his camera taken and the film exposed. Finally one person dipped a rag in gasoline obtained from a motorcycle parked nearby and threw the burning rag in the ROTC building. At 8:30 p.m., the building was on fire, however, the Kent Fire Department's records indicate that it was not notified until 8:49 p.m. The fire department sent trucks to the scene. Upon arrival, the firemen were harassed and had their fire hoses taken forcibly from them and cut. At approximately 9:00 p.m.,(3) the Kent University Police Department which had two 12 man squads in the area but had to this time taken no action, moved to the scene of the ROTC building in an attempt to protect the firemen(3a) and disperse the crowd. As they arrived, the firemen left the ROTC building which was not yet ablaze. The Kent University policemen were joined at 9:17 by ten men from the Portage County Sheriff's Office. (At 8:40, twenty state policemen had been sent to the Campus, but not the commons area. Apparently they were in the vicinity of the President's home.) Together they fired tear gas at the crowd and at about 9:30 p.m., drove it in a northeasterly direction across the commons where a small athletic shed was set on fire. Four Kent State University policemen were injured by rocks, but none was hurt seriously. Much of the crowd continued toward the downtown area of Kent, but others attempted to put out the fire started in the athletic shed.

In the absence of the firemen, at about 9:45 p.m., the ROTC building flared up and began to burn furiously. The fire department returned to the Campus between 10:00 p.m. and 10:20 p.m., but the building was consumed. By 10:30 p.m. at least 400 members of Company A and Company C, 145th Infantry and Troop G, 107th Armored Cavalry, Ohio National Guard had arrived in Kent. Company A and Troop G were sent to the vicinity of the ROTC building. Troops G's convoy was stoned as it approached the Campus. Eight Guardsmen were injured by rocks and flying glass-at least one of whom required medical attention. Some members of the crowd, about 200, who were prevented by law enforcement agencies from going to the downtown area of Kent, returned to the ROTC building. At about 10:30 p.m., they were dispersed b tear gas fired by members of the National Guard and Sheriff's Department. By 11:00 p.m., all members of the crowd had fully dispersed and the Campus was quiet. At some time between 9:30 and 11:30 p.m. about 100 Ohio state police had swept the Campus and found no demonstrators. By 3:00 a.m., May 3, 1970, 60-70 Ohio State policemen, all members of the Sheriff's Office, and all members of Troop G had been released from duty. Some members of Company A and 20 members of the Ohio State Highway Patrol established roving patrols and posted men at various points on the perimeter of the Campus. They remained on duty until 6:00 a.m., Sunday, May 3, 1970.

Thus far, there have been identified 13 persons involved in the burning of the ROTC building and the harassment of firemen; some of the identified persons are high school students from Ohio who were possibly on LSD at the time of the burning. One person is alleged to be the principal narcotics peddler in Kent. None of the victims of the shooting incident have been implicated in the unlawful burning of the ROTC building.(4) In addition, none has been identified as an out of state, non-students as having any part in the unlawful burning [sic].

At 10:30 a.m., Sunday morning, May 3, 1970, Governor Rhodes, Portage County Prosecutor Ronald Kane, representatives from the highway Patrol and National Guard, City officials, University officials and others held a conference in Kent. A decision was reached to keep the University open for classes. Governor Rhodes advised Dr. White, President of Kent State, of this fact at approximately 12:00 noon, May 3, 1970. We are informed that subsequent to this meeting, Governor Rhodes held a press conference at which time he accused three or four agitators of plotting the disruptions and of attempting to close the University down. He was apparently referring to the "Kent Four" just released from jail. Rhodes pledged to use every force of law to restore the situation.

From 6:00 a.m. until 6:00 p.m., both Troop G, 107th Armored Cavalry and Company C, 145th Infantry patrolled the Campus and the City of Kent. So far as we are aware, no incidents occurred during this time period. Company A, 145th Infantry was not on duty from 6:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m.

At sometime during May 3rd, 1970, Robert Matson, Vice-President for Student Affairs and Frank Frisina, President of the Student Body issued a "special message to the University community." This "special message" informed the students and faculty that the Governor, through the National Guard, had assumed control of the Campus. They further reported that (a) all forms of rallies and outdoor demonstrations-whether peaceful or otherwise-were prohibited and that (b) although the curfew in the City was in effect 8:00 p.m. to 6:00 a.m., the curfew in effect on the Campus was from 1:00 a.m. to 6:00 a.m. It is not known what person(s) decided that assemblies of all kinds would be prohibited nor do we know under what authority this decision was made, nor what distribution the "special message" received. There are indications that it was posted on University buildings. Some members of Company C and of Troop G were recalled to duty to supplement Company A which had come on duty at 6:00 p.m. Approximately 50 sheriff's deputies were sent to Kent at 8:30 p.m.

At about 8:30 p.m., Sunday, a group of persons began gathering on the commons. Some were going from dorm to dorm to gather more people.

At about 9:15 p.m., Kent State University Police Officers read to the gathered persons, approximately 1000-1500, the Riot Provisions of Ohio law and ordered them to disperse. The crowd then moved to the home of President White where they were dispersed by tear gas by state police. From this location the group apparently splintered. Some attempted to go downtown and got to the corner of Lincoln and Main Streets, adjacent to the Campus, where they were halted by law enforcement officers. This was at approximately 11:00 p.m. It is possible that some students had been sitting down at this location from as early as 9:00 p.m. Law enforcement officers from the city and county faced the students while National Guardsmen took a position behind them. State police helicopters were overhead with searchlights being played on the crowd. Subsequently, one student obtained a bullhorn from the law enforcement officers and read to the students a list of demands; each such demand was greeted with applause. The demands read were that:

1. The ROTC program be removed from campus;

2. Full amnesty be granted for all persons arrested Saturday night;

3. All demands, whatever they might be, of BUS (Black United Students), be

met;

4. The National Guard be removed from the campus by Monday night;

5. The curfew be lifted;

6. Tuition for all students be decreased.

Subsequently, a student (possibly the same one) spoke with police officers and thereafter announced by bullhorn to the students that the National Guard would be immediately leaving the front Campus and that, in response to their demands that they speak with Mayor Satrom, President White and/or Governor Rhodes, Mayor Satrom was on his way to the gathering of students and that they were still looking for President White. It seems that many students then moved onto the Campus, thinking that an agreement had been reached. Shortly thereafter, a law enforcement officer or National Guardsman, probably the latter, announced over a loudspeaker that the curfew had been moved two hours, from 1:00 a.m. to 11:00 p.m., and that the students were to disperse immediately. This announcement was greeted with anger, obscenities and rocks, at which time the National Guard fired tear gas into the crowd and advanced upon them with bayonets. About 200 students attempted to escape into the library located at the intersection of Lincoln and Main. Two students were probably bayoneted at this time. Most of the other students retreated slowly toward their dormitories; others, however, remained to be arrested. The students who went into the library were later removed by the Highway Patrol peacefully and without arrests.

At least one group of about 300 students was pursued with tear gas by the National Guard through the Campus to the area of the Tri-Tower dormitories, where they were hesitantly allowed entrance to escape the tear gas. Allison Krause was among these persons.

By 1:00 a.m., Monday, May 4, 1970, the Campus was quiet. Fifty-one persons were arrested for curfew violations. The members of Troop G and Company C who were recalled to duty about 8:30 p.m. were released. Company A continued its regular duty.

At 6:00 a.m., May 4, 1970, the Ohio State Highway Patrol had 20 men on the Campus. Company A was relieved of duty by Company C and Troop G, both of which had moved-at least in part-early that morning from their bivouac areas off campus to the football stadium on the Campus. Company A was to move from the gymnasium to the football stadium immediately after they came off duty at 6:00 a.m. It is believed that this move was partially accomplished by Company A. Morning gym classes were canceled because of the presence of National Guard troops in the gym and at the time of the shooting some unknown number of National Guardsmen were located in the gymnasium. As of Monday morning, May 4, 1970, approximately 850 National Guardsmen were located on the Kent State Campus.

At 10:00 a.m. a meeting was held among representatives of Kent State University, Ohio National Guard, the Ohio State Highway Patrol and city officials. At this time, a uniform curfew of 8:00 p.m. to 6:00 a.m., applicable both to the city and the Campus, was agreed upon and the Mayor's Proclamation of Civil Emergency, dated May 2, 1970 was modified to reflect this change. Also at this meeting, an unknown representative of Kent State University requested that the rally rumored to be held at 12:00 noon not be allowed to be held.(5) However, subsequent information suggests that it was the O.H.N.G. who determined that the rally would not be held.

During the weekend, word had been orally passed that there was to be a rally on the commons at 12:00 noon, Monday, May 4, 1970, in protest of any or all of the following:

1. The invasion of Cambodia by the U.S.

2. The presence of the National Guard on Campus

3. The ROTC program on campus

4. Research at the Liquid Crystals Institute (which, rumor had it, had to

do with developing body heat detectors for use in jungle warfare).(6)

By 10:30 a.m., a few students had gathered on the commons and by 11:30 a.m., students began ringing the Victory Bell to attract other students to the commons area. At about 11:30 a.m., some members of Company C and Troop G, on patrol since 6:00 a.m., were told to move to the ROTC building. Company A, relieved from duty at 6:00 a.m. had the opportunity to receive about three hours sleep when some of its members also were told to move to the ROTC building. The troops were moved into position around the ROTC building facing the students about 175 yards away at about 11:45 a.m. Ninety-nine men from the National Guard were present; 53 from Company A, 25 from Company C and 18 from Troop G, al led by General Canterbury, Lt. Col. Fassinger and Major Jones. Apparently no plan for dispersing the students was formulated.

Most persons estimate that about 200-300 students were gathered around the Victory Bell on the commons with another 1,000 or so students gathered on the hill directly behind them.(7) Apparently, the crowd was without a definite leader, although at least three persons carried flags. An unidentified person made a short speech urging that the university be struck. We are not aware of any other speeches being made. The crowd apparently was initially peaceful and relatively quiet.

At approximately 11:50 a.m., the National Guard requested a bullhorn from the Kent State University Police Department. An announcement was made that the students disperse but apparently it was faint and not heard since it evoked no response from the students.(8) Consequently, three National Guardsmen and a Kent State University Policeman got in a jeep and, again using the bullhorn to order the students to disperse, drove past the crowd. This announcement was greeted with cries of "Fuck you" and many students made obscene gestures. Victim Jeff Miller was one of this group. The jeep drove past the students, a second time. At this time, the students in unison sang/chanted "Power to the people. Fuck the pigs." The announcement to disperse was made a 3rd time at which time the students chanted "One, two, three, four, we don't want your fucking war," and after which they continuously chanted "Strike, strike..." The jeep then apparently came closer to the crowd saying clearly, "Attention. This is an order. Disperse immediately. This is an order. Leave this area immediately. This is an order. Disperse." This was greeted with cries of "Fuck you." The above announcements were again repeated at which time the students responded "Pigs off campus." The Kent State University Policemen then announced, "For your own safety, all you bystanders and innocent people, leave." The crowd replied with chants of "Sieg Heil."

At some point when the jeep drove by the crowd of students, a few rocks were thrown at it-one hitting the jeep and a second striking a Guardsman but doing no damage. Major Jones of the National Guard, after one last above announcement had been made and probably in response to the rock throwing, ran out to the jeep and ordered it to return to the line.

About five grenadiers were ordered to fire tear gas from M-7 grenade launchers toward the crowd. The projectiles apparently fell short and caused the students to retreat only slightly up Blanket Hill in the direction of Taylor Hall. Some students ran to Verder Hall, ripped up sheets and moistened them to use as gas masks. Some students, a few with gas masks, and others with wet rags over their faces retrieved the tear gas canisters and threw them back in the direction of the National Guard. This action brought loud cheers from the students as the Victory Bell. They also chanted "Pigs off campus." Again an announcement was made over a loudspeaker ordering the students to disperse. The students responded by chanting "Sieg Heil" and "One, two, three, four, we don't want your fucking war." They also sung/chanted "Power to the people. Fuck the pigs."

Between 12:05 p.m. and 12:15 p.m., the 96 men of Companies A and C, 145th Infantry and of Troop G, 107th Armored Cavalry were ordered to advance. Bayonets were fixed and their weapons were "locked and loaded," with one round in the chamber, pursuant to rules laid down by the Ohio National Guard. All wore gas masks. Some carried .45 pistols, most carried M-1 rifles, and a few carried shotguns loaded with 7 1/2 birdshot and double ought buckshot. One major also carried a .22 Beretta Pistol.

Prior to the advance of the National Guard, 30 Ohio State Highway Patrolmen were positioned behind them to make any necessary arrests. They did not advance with the Guard. Also prior to the advance, Company C was instructed that if any firing was to be done, it would be done by one man firing in the air (presumably on the order of the officer in charge). It is not known any instructions concerning the firing of weapons was given to either Company A or Troop G [sic].

As the National Guard moved out from the ROTC building, Company A was on the right flank, Company C was on the left flank and Troop G was between the two. General Canterbury moved with the troops. As they approached the students, tear gas was fired at the crowd. The combination of the advancing troops and the tear gas forced the students to retreat. Some students retreated up Blanket Hill to the northeast of the advancing troops. The majority of students were forced up Blanket Hill to the south of Taylor Hall. Some rocks were thrown by the students at the National Guard at this time but were for the most part ineffective.(9)

As the Guard approached the bottom of Blanket Hill at the southwest corner of Taylor Hall, it split into two groups, each following the two main groups of students. Twenty-three members of Company C, under the command of Major Jones, moved around the northwest side of Taylor Hall and attempted to disperse the small crowd of students who had moved in this direction. They encountered little hostility although some rocks were thrown at them and some of their tear gas canisters were returned. They reached a position on Blanket Hill slightly to the north and west of Taylor Hall and remained there throughout the incident. None of these 23 Guardsmen fired their weapons.

Fifty-three members of Company A, 18 members of Troop G and two members of Company C, all commanded by General Canterbury and Lt. Col. Fassinger moved to the south and east of Taylor Hall, pursuing the main body of students who retreated between Taylor and Johnson Halls. The great mass of students, upon reaching the southeast corner of Taylor Hall, merely opened their ranks and allowed the National Guard to Pass between them; others, for safety of because they had been tear gassed took refuge in various buildings; a large number of students retreated down the hill in front of Taylor Hall. The main body of National Guardsmen continued past Taylor Hall driving this last group of students in two directions. One group of students retreated to a paved parking lot south of Prentice Hall and from there into a gravel or rock parking lot south of Dunbar Hall. The other group retreated to the area of a football practice field southeast and approximately 150 yards from Taylor Hall. The National Guardsmen apparently momentarily halted to allow the students on the practice field time to pass through the two gates in the fence surrounding the field. The Guard then moved down the steep incline from Taylor Hall and onto the field where it took up a position in the northeastern portion of the field close to the fence. This second group of Guardsmen was hit with some rocks on its way to the fence from its initial starting point; seven Guardsmen claim they were hit with rocks at this time. They were also cursed constantly.

Some of the students who had retreated beyond the fence obtained rocks and possibly other objects from the parking area south of Dunbar Hall and from a construction site about 7 yards southeast of the practice football field. They then returned to within range of the Guard and began to pelt them with objects. The number of rock throwers at this time is not known and the estimates range between 10 and 50. Victim Dean Kahler and Barry Leving, boyfriend of Victim Allison Krause, threw rocks at the Guard. Debris, similar in composition to rocks found on the Kent State Campus, was found in the pockets of the jacket that Allison Krause was wearing. The rock throwers received encouragement from many of the other students who had retreated, but who did not take part in the rock throwing. Victims Canfora, Stamps and Grace were probably among this group waving flags and shouting encouragement. We believe that the rock throwing reached its peak at this time. Four Guardsmen claim they were hit with rocks at this time. Fourteen others claim they were hit with rocks but do not state when they were hit. We believe that it is probably that most were hit while they were positioned on the football practice field.

Because of the number of rocks thrown, every other Guardsman was ordered to face in an opposite direction to watch for missiles. Some rocks were thrown back at the students by the Guard. The majority of students who had merely stood aside and allowed the Guard to pass through their ranks massed on the hill in front of Taylor Hall to observe the Guardsmen and other students. Thus, the Guard appeared to be flanked on three sides by students while the Guard was on the practice field.

The Guard shot tear gas at the students in the parking lot and at those to the south of them during the approximately 10 minutes on the practice field. It was as far as we can tell, ineffective. A small amount of tear gas was also fired without result at the mass of onlookers gathered in front of Taylor Hall. On one such occasion, the canister was thrown back by a student, picked up by a National Guardsman, and thrown again at the students, and again was thrown back at the Guard. This "tennis match" was accompanied by loud cheering and laughing from the students.

Just prior to the time the Guard left its position on the practice field, members of Troop G were ordered to kneel and aim their weapons at the students in the parking lot south of Prentice Hall. They did so, but did not fire. One person, however, probably an officer, at this point did fire a pistol in the air. No Guardsman admits firing this shot. Major Jones admitted drawing his .22 at about this time, but stated that he did not fire it. Although Major Jones had been with Company C at the top of Taylor Hall hill, he walked through the crowd to find out if General Canterbury wanted assistance.

The Guard was then ordered to regroup and move back up the hill past Taylor Hall. Interviews indicate that they moved into a formation whereby every other person faced Taylor Hall while the others faced the area of the practice field. Photographs, however, show most Guardsmen facing Taylor Hall. The students at this time apparently took up the chant, "One, two, three, four, we don't want your fucking war." Many students believed that the Guard had run out of tear gas and they began to follow the Guard up the hill.

Some Guardsmen, including General Canterbury and Major Jones, claim that the Guard did run out of tear gas at this time. However, in fact, it had not. Both Captain Srp and Lieutenant Stevenson of Troop G were aware that a limited supply of tear gas remained and Srp had ordered one canister loaded for use at the crest of Blanket Hill. In addition, Sp/4 Russell Repp of Company A told a newsman that he alone had eight canisters of tear gas remaining. This has not been confirmed. Repp did not mention tear gas when he was interviewed by the FBI.

Some rocks were thrown as they moved up the hill and seven Guardsmen claim that they were struck at this time. The crowd on top of the hill parted as the Guard advanced and allowed it to pass through, apparently without resistance. When the Guard reached the crest of Blanket Hill by the southeast corner of Taylor Hall at about 12:25 p.m., they faced the students following them and fired their weapons. Four students were killed and nine were wounded.

The few moments immediately prior to the firing by the National Guard are shrouded in confusion and highly conflicting statements. May Guardsmen claim that they felt their lives were in danger from the students for a variety of reasons-some because they were "surrounded," some because a sniper fired at them; some because the following crowd was practically on top of them; some because the "sky was black with stones;" some because the students "charged" them or "advanced upon them in a threatening manner;" some because of a combination of the above. Some claim their lives were in danger, but do not state any reason why this was so.

Approximately 45 Guardsmen did not fire their weapons or take any other action to defend themselves.(10) Most of the National Guardsmen who did fire their weapons do not specifically claim that they fired because their lives were in danger. Rather, they generally simply state in their narrative that they fired after they heard others fire or because after the shooting began, they assumed an order to fire in the air had been given. As a general rule, most Guardsmen add the claim that their lives were or were not in danger to the end of their statements almost as an afterthought.

Six Guardsmen, including two sergeants and Captain Srp of Troop G stated pointedly that they lives of the members of the Guard were not in danger and that it was not s shooting situation. The FBI interviews of the Guardsmen are in many instances quite remarkable for what is not said, rather than what is said. Many Guardsmen do not mention the students or that the crowd or any part of it was "advancing" or "charging." Many do not mention where the crowd was or what it was doing.

We have some reason to believe that the claim by the National Guard that their lives were endangered by the students was fabricated subsequent to the event. The apparent volunteering by some Guardsmen of the fact that their lives were not in danger gives rise to some suspicions. One usually does not mention what did not occur. Additionally, an unknown Guardsman, age 23, married, and a machinist by trade was interviewed by members of the Knight newspaper chain. He admitted that his life was not in danger and that he fired indiscriminately into the crowd. He further stated that the Guardsmen had gotten together after the shooting and decided to fabricate the story that they were in danger of serious bodily harm or death from the students. The published newspaper article (see Appendix 1) quoted the Guardsman as saying:

"The guys have been saying that we got to get together and stick to the same story, that it was our lives or them, a matter of survival. I told them I would tell the truth and wouldn't get in trouble that way."

Also, a chaplain of Troop G spoke with many members of the National Guard and stated that they were unable to explain to him why they fired their weapons. We do not know the specific individuals with whom the chaplain spoke.

As with the Guardsmen, the students tell a conflicting story of what happened just prior to the shootings. A few students claim that a mass of students who had been following the Guard on its retreat to Taylor Hall from the practice football field suddenly "charged" the Guardsmen hurling rocks. These students allege in general that the Guard was justified in firing because otherwise they might have been overrun by the on rushing mob.

A few other students claim that the students were gathered in the parking lot south of Prentice Hall-a distance of 80 yards or better from the Guard-when some of the Guardsmen suddenly turned and fired their weapons at the gathered crowd. They generally either do not mention rock throwing or say that it was light and ineffective.

A plurality of students give the general impression that the majority of students following the Guard were located in and around the parking lot south of Prentice Hall. They also state that a small group of students-perhaps 20 or 25-ran in the direction of the Guard and threw rocks at them from a moderate to short distance. The distance varies from as close as 10 to 50 feet or more. However, as will be discussed later in detail, available photographs indicate that the nearest student was 60 feet away. At this time, they allege that the Guard began firing at the students.

There are certain facts that we can presently establish to a reasonable certainty. It is undisputed that the students who had been pursued by Troop G and Company A in turn followed the Guardsmen as they moved from the practice football field to Taylor Hall. Some rocks wee thrown and curses were shouted. No verbal warning was given to the students immediately prior to the time the Guardsmen fired. We do not know whether the bullhorn had been taken by the Guard from the ROTC building. No effort was made to obtain Company C's assistance.(11) There was no tear gas fired at the students, although, as noted, at least some Guardsmen, including two officers in Company G, were aware that a limited number of canisters remained. There was no request by any Guardsman that tear gas be used.

There was no request from any Guardsman for permission to fire his weapon. Some Guardsmen, including some who claimed their lives were in danger and some who fired their weapons, had their backs to the students when the firing broke out. There was no initial order to fire.(12) One Guardsman, Sgt. McManus, stated that after the firing began, he gave an order to "fire over their heads."

The Guardsmen were not surrounded. Regardless of the location of the students following them, photographs and television film show that only a very few students were located between the Guard and the commons. They could easily have continued in the direction in which they had been going. No Guardsman claims he was hit with rocks immediately prior to the firing, although one Guardsman stated that he had to move out of the way of a three inch "log" just prior to the time that he heard shots. Two Guardsmen allege that they were hit with rocks after the firing began. One student alleges that immediately subsequent to the shooting he moved to the Guard's position and looked for rocks and other debris. He claims he saw only a few.

Although many claim they were hit with rocks at some time during the confrontation, only one Guardsman, Lawrence Shafer, was injured on May 4, 1970, seriously enough to require any kind of medical treatment. He admits his injury was received some 10 to 15 minutes before the fatal volley was fired. His arm, which was badly bruised, was put in a sling and he was given medication for pain. One Guardsman specifically states that the quantity of rock throwing was not as great just prior to the shooting as it had been before.

There was no sniper. Eleven of the 76 Guardsmen at Taylor Hall claim that they believed they were under sniper fire or that the first shots came from a sniper. Two lieutenants of Company A, Kline and Fallon, claim they heard shots from a small caliber weapon and saw the shots hitting the ground in front of them. Lt. Fallon specifically claims the shots came from the parking lot south of Prentice Hall. Sgt. Snare of Company A was facing away from the students when, he alleges, something grazed his right shoulder. He claims it was light and fast and traveled at a severe angle to the ground near his right foot. He stated at the time he thought it might have been a bullet. Captain Martin and Sp/4 Repp of Company A claim they heard what they thought were small caliber weapons form the Johnson-Lake Hall area. Others including General Canterbury merely state the first shot was fired by a small caliber weapon.(14)

A few Guardsmen do not state that they thought the first shot was from a sniper, but do state that the first shot, in their opinion, did not come from an M-1 rifle; in this connection, it is alleged that the sound was muffled or that it came from what they thought was an M-79 grenade launcher, converted for firing tear gas. Some construction workers also reported hearing fire from a small caliber weapon prior to the firing by the National Guard. The great majority of Guards do not state that they were under sniper fire and many specifically state that the first shots came from the national Guardsmen.

The FBI has conducted an extensive search and has found nothing to indicate that any person other than a Guardsman fired a weapon. As a part of their investigation, a metal detector was used in the general area where Lieutenants Kline and Fallon indicated they saw bullets hit the ground. A .45 bullet was recovered, but again nothing to indicate it had been fired by other than a Guardsman. Students and photographers on the roofs of Johnson and Taylor Halls state there was no sniper on the roofs.

At the time of the shooting, the National Guard clearly did not believe that they were being fired upon. No Guardsman claims he fell to the ground or took any other evasive action and all available photographs show the Guard at the critical moments in a standing position and not seeking cover. In addition, no Guardsman claims he fired at a sniper or even that he fired in the direction from which he believed the sniper shot. Finally, there is no evidence of the use of any weapons at any time in the weekend prior to the May 4 confrontation; no weapon was observed in the hands of any person other than a Guardsman, with the sole exception of Terry Norman, during the confrontation. Norman, a free lance photographer, was with the Guardsmen most of the time during the confrontation. A few students observed his weapon and claim that he fired at students just prior to the time the Guardsmen fired. Norman claims that he did not pull his weapon until after the shooting was over and then only when he was attacked by four or five students. His gun was checked by a Kent State University Policeman and another law enforcement officer shortly after the shooting. They state that his weapons had not been recently fired.

While we do not presently know the exact nature or extent of the riot control training given to the Guardsmen on the line at Taylor Hall, most had received some training. Both Company A and Company C, 145th Infantry received at least 16 hours in riot control training in 1968 and 1969. We don't know how much training, if any, was received before that. Troop G, since September, 1967 has received a total of 52 hours in riot control training-32 hours in 1967, 10 hours in 1969 and 10 hours in 1970. We do not know exactly of what lectures and demonstrations this training consisted, but we are fairly certain that the Guardsmen were instructed to some extent in (a) Riot Control measures and the Application of Minimum Force (b) Riot Control Agents and Munitions and (c) Riot Control under extreme conditions.

Although we believe that the use of minimum force was covered in lectures, we have in our possession a copy of a briefing required to be read verbatim to all troops immediately prior to their employment in a civil disturbance. The orders which they receive are conflicting wit regard to the use of weapons. The briefing provides as follows:

"f. Weapons

(2) Indiscriminate firing of weapons is forbidden. Only single aimed shot

confirmed targets will be employed.

Potential targets are:

(c) Other. In any instance where human life is endangered by the forcible,

violent actions of a rioter, or when rioters to whom the Riot Act (of Ohio)has

been read cannot be dispersed by any other reasonable means, then shooting

is justified."

This latter statement is in accord with Section 2923.5, Ohio Revised Code which provides that any law enforcement officer or member of the Militia is "guiltless for killing, maiming or injuring a rioter as a consequence of the use of such force as is necessary and proper to suppress the riot or disperse or apprehend rioters." We are relatively sure that all National Guardsmen received training in the legal consequences of their actions while in an active duty status, which training included permission to fire as described above. All National Guardsmen tell us that they have authorization to fire wen their lives are in danger. In order to clarify and make sense of these conflicting instructions, all Guard instructors must be interviewed in detail concerning their lectures regarding the discharge of weapons into a crowd of persons.

Each person who admitted firing into the crowd has some degree of experience in riot control. None are novices. Staff Sergeant Barry Morris has been in the Guard for 5 years, 3 month. He has received at least 60 hours in riot control training and has participated in three previous riots. James Pierce has spent 4 years, 9 months in the Guard. He has an unknown, but probably substantial, number of hours of riot control training and has participated in one previous riot. Lawrence Shafer has been in the Guard for 4 1/2 years. He has received 60 hours of rot control training and has participated in three previous riots. Ralph Zoller has been in the Guard for 4 years. He has received 60 hours of riot training and has participated in two previous riots. All are in G Troop. We do not know how much, if any, riot control training or experience William Herschler has.

In trying to solve the puzzle of the location of the students prior to the shooting, we observed many photographs and contact strips obtained during the investigation by the FBI. There is, however, a curious lack of photographs from the time the Guard left the practice football field until the time of the shooting. We do have at least 3 photographs of this period that are helpful. They are attached to this report. The first is a photograph of a portion of the parking lot south of Prentice Hall and of a portion of the hill in front of Taylor Hall taken within an estimated 15-30 seconds prior to the firing. The second photograph was taken from Taylor Hall immediately after the shooting started and while it was going on. It shows victim Joseph Lewis standing 20 yards away from the Guard just before he was shot. The third photograph was taken from Prentice Hall shortly after the shooting was over. No crowd or mass of people-close to the Guard or otherwise-is identifiable in this photograph. We do not know exactly how long after the shooting this picture was taken.

A minimum of 54 shots were fired by a minimum of 29 of the 78 members of the National Guard at Taylor Hall in the space of approximately 11 seconds. Fifteen members of Company A admit they fired but all claim that they fired either in the air or into the ground. However, William Herschler of Company A is alleged by Sergeant McManus of his Company to have emptied his entire clip of 8 rounds into the crowd-firing semi-automatically. The National Guard says his weapon was fired and Herschler, who was taken to the hospital after the shooting suffering from hypertension, kept repeating in the ambulance that he had "shot two teenagers." We do not yet know who checked Herschler's weapon to determine whether it was fired. The only two members of Company C who were on the southeast side of Taylor Hall admit they fired their weapons but claim they did not fire at the students.

Seven members of Troop G admit firing their weapons, but also claim they did not fire at the students. Five persons interviewed in Troop G, the group of Guardsmen closest to Taylor Hall, admit firing a total of eight shots into the crowd or at a specific student.

SP/4 James McGee claimed that it looked to him like the demonstrators were overrunning the 107th. He then saw one soldier from Company A fire four or five rounds from a .45 and saw a sergeant from Troop G also fire a .45 into the crowd. He claims he then fired his M-1 twice over the heads of the crowd and later fired once at the knee of a demonstrator when he realized the shots were having no effect.

SP/4 James Pierce, a Kent State student, claims that the crowd was within ten feet of the National Guardsmen. He then heard shot form the National Guard. He then fired four shots-one into the air; one a male ten feet away with his arm drawn back and a rock in his hand(this male and appeared to get hit again); he then turned to his right and fired into the crowd; he turned back to his left and fired at a large Negro male about to throw a rock at him.

Staff Sergeant Barry Morris claims the crowd advanced to within 30 feet and was throwing rocks. He heard a shot which he believes cam from a sniper. He then saw a 2nd Lieutenant step forward and fire his weapon a number of times. Morris then fired two shots from his .45 "into the crowd."

Sergeant Lawrence Shafer heard three or four shots come from his "right" side. He then saw a man on his right fire one shot. He then dropped to one knee and fired once in the air. His weapon failed to eject and he had to eject the casing manually. He then saw a male with bushy, sandy hair, in a blue shirt (Lewis) advancing on him and making an obscene gesture (giving the finger). This man had nothing in his hands. When this man was 25-35 feet away, Shafer shot him. He then fired three more times in the air.

In addition to Herschler, at least one person who has not admitted firing his weapon, did so. The FBI sib currently in possession of four spent .45 cartridges which came from a weapon not belonging to any person to any person who admitted he fired. The FBI has recently obtained all .45's of persons who claimed they did not fire, and is checking them against the spent cartridges.

In addition, the Guardsman previously mentioned who was interviewed by a reporter from the Knight newspaper chain told the interviewer that he "closed his eyes" after other Guardsmen fired and that he, too, fired one shot "into the crowd." Of all Guardsmen who admit firing into the crowd, the physical description of this unknown Guardsman might match only that of William Zoller. However, it is likely that it is not Zoller. Zoller's story to the FBI does not match that of this unknown Guardsman.

The reaction by the leadership of the National Guard was immediate when the shooting began. Both Major Jones and General Canterbury immediately ordered a cease fie and kept repeating that order. Major Jones ran out in front of the Guardsmen and began hitting their weapons with his baton. Some Guardsmen (unknown as yet) had to be physically restrained from continuing to fire their weapons.

Sergeant Robert James of Company A, assumed he'd been given an order to fire, so he fired once in the air. As soon as he saw that some of the men of the 107th were firing into the crowd, he ejected his remaining seven shells so he would not fire any more. Sergeant Rub Morris of Troop G prepared to fire his weapon but stopped when he realized that the "rounds were not being placed." Sergeant Richard Love of Company C fired once in the air, then saw others firing into the crowds; he asserted he "could not believe" that the others were shooting into the crowd, so he lowered his weapon.

When the firing began, many students began running; others hit the ground. Because they believed the National guard was firing blanks, some remained standing until they hear bullets striking around them. The firing continued for about 11 seconds.

Four students wee killed, nine others were wounded, three seriously. Of the students who were killed, Jeff Miller's body was found 8-90 yards from the Guard. Allison Krause fell about 100 yards away. William Schroeder and Sandy Scheuer were approximately 130 yards away from the Guard when they were shot.

Although both Miller and Krause had probably been in the front ranks of the demonstrators initially, neither was in a position to pose even a remote danger to the National Guard at the time of the firing. Sandy Scheuer, as best as we can determine, was on her way to a speech therapy class. We do not know whether Schroeder participated in any way in the confrontation that day.

Miller was shot while facing the Guard. The bullet entered his mouth and exited at the base of the posterior skull. Both Krause and Scheuer were shot form the side. The bullet that killed Allison Krause penetrated the upper left arm and then into the left lateral chest. The bullet which killed Sandy Scheuer entered the left front side of her neck and exited the right front side. William Schroeder was shot while apparently in a prone position, facing away from the Guard. The bullet entered his left back at the 7th rib and some fragments exited at the top of his left shoulder.

Of the nine students who were wounded, Joseph Lewis was probably the closest to the Guard. He was shot while making an obscene gesture about 20 yards from the National Guard. Two bullets struck Lewis. One entered his right lower abdomen and exited from his left buttock. The second projectile caused a through and though wound in Lewis' lower left leg, about four inches above the ankle.

John Cleary was located by a metal sculpture in front of Taylor Hall approximately 37 yards from the National Guard when he was shot. He was apparently standing laterally to the Guard and facing Taylor Hall when he was shot. The bullet entered his left upper chest and the main fragments exited from the right upper chest.

Allen Canfora was positioned by the FBI about 75 yards away from the Guard when he received a through and through wound of the right wrist.(15) His injury was minor.

Dean Kahler was located about 95-100 yards from the Guard when he was shot. Kahler was struck in the left posterior side and the projectile, traveling slightly from back to front and from above to below, fractured three vertebrae. Kahler is currently paralyzed from the waist down. He will probably remain a paraplegic.

Douglas Wrentmore was located about 110 yards from the Guard when he was shot. The bullet entered the left side of Wrentmore's right knee, caused a compound fracture of the right tibia and exited on the right side of the knee.

Donald MacKenzie was shot while running in the opposite direction from the Guard. He was approximately 245-250 yards away from the Guard. The projectile which struck MacKenzie entered the left rear of his neck, struck his jawbone and exited through his cheek. Dr. Ewing, MacKenzie's attending physician, has expressed an opinion that MacKenzie was snot shot by a projectile from a military weapon. This opinion has been challenged in an unsubstantiated newspaper article by other physicians on a purely theoretical basis. No bullet fragments were available for analysis.

James Russell was wounded near the Memorial Gymnasium, an area 90 degrees removed from the locations of other students who were shot. He was about 125-130 yards from the Guard when he was shot. He had two wounds-a small puncture would in the right thigh which may have been caused by a projectile; however, no projectile was located; the other wound was located on the right forehead. A very small projectile is still located in Russell's head. We theorize that it may have been caused by 7 1/2 birdshot. His injuries were minor.

Two other students, Thomas Grace and Robert Stamps, were wounded but as of yet, we have been unable to place either with any accuracy on the field. We are relatively sure that Stamps was shot while he was in the parking lot south of Prentice Hall. He was probably about 165 yards away when he was shot. The projectile struck Stamps from the rear in the right buttock and penetrated four inches. The attending physician expressed the opinion that Stamps was struck by a projectile from a low velocity weapon but the FBI's lab analysis shows the bullet came from a military weapon.

Thomas Grace was shot in the back of the left ankle and fragments from the projectile exited from the top of his foot. The FBI has tentatively placed Grace directly in front of the Guard at a distance of 20 yards from them. However, it is noted that the Akron Beacon Journal placed Grace in the parking lot south of Prentice Hall-over 100 yards from the Guard. Since Grace has refuse to place himself on the field, we have no way of knowing his position. In all, only Lewis and Miller were shot from the front. Seven students were shot from the side and four were shot from the rear.

There is no ballistics evidence to prove which Guardsmen shot which student. We can, however, show that Shafer shot Lewis, but only because their statements to the FBI coincide. We will not be able to determine who shot the other students.

Of the 13 Kent State students shot, none, so far as we know, were associated with either the disruption in Kent on Friday night, May 1, 1970, or the burning of the ROTC building on Saturday, May 2, 1970.

On the day of the shooting, Jeffrey Miller and Allison Krause can be placed at the front of the crowd taunting the National Guardsmen. Miller made some obscene gestures at the Guardsmen and Krause was heard to shout obscenities at them. Victims Grace, Canfora and Stamps were, we believe, active in taunting the Guard. Grace and Canfora probably had flags and were encouraging the students to throw rocks at the Guardsmen. Dean Kahler admitted to the FBI that he had thrown "two or three" rocks at the Guardsmen at the Guardsmen at some time prior to the shooting. Joseph Lewis at the time of the shooting was making an obscene gesture at the Guard.

As far as we have been able to determine, Schroeder, Scheuer, Cleary, MacKenzie, Russell and Wrentmore were merely spectators to the confrontation.

Aside entirely from any questions of specific intent on the part of the Guardsmen or a predisposition to use their weapons, we do not know what started the shooting. We can only speculate on the possibilities. For example, Sergeant Leon Smith of Company A stated that he saw a man about 20 feet from him running at him with a rock. Sergeant Smith then says he fired his shotgun once in the air. He alone of all the Guardsmen does not mention hearing shooting prior to the time he fired. He asserts that "at about the same time" he fired, others fired. Some Guardsmen claim that the first shot sounded to them as if it came from a M-79 grenade launcher-a sound probably similar to that made by a shotgun.